An Interview with Director Alystyre Julian

ON RIDING ALONG IN THE SIDECAR

Anne Waldman has had a huge body of work, but this ten-year period I’ve lived in the making of this documentary came right after the completion of her epic work The Iovis Trilogy: Colors in the Mechanism of Concealment (2011). It’s an epic feminist work and three books combined—a trilogy about war and patriarchy. She had also just published Manatee / Humanity) (2009). In this particular period, there is so much depth in each work around a particular set of themes—whether it’s the endangered species of the manatee—or her passion for the archive. And the way it happens on the page. There’s nothing predictive about the way she uses language and the way her poems are. They exist on the page and they exist in her performance in another way entirely. She improvises with the words off the page. This whole process has been a master class. I’ll be reading her work for the rest of my life. And it feels like I lived it in a really embodied way. Because I was right there—riding in the sidecar.

ON LIGHTNING STRIKING AT THE BOWERY POETRY CLUB

I went to one particular reading by Anne Waldman and Ann Lauterbach at the Bowery Poetry Club in 2009. That was the impetus. I'd been to Naropa as a young poet and had heard Waldman read before. But at this particular reading—lightning struck. I felt this vibration, the frequency she was operating on. The streaming of her language, her embodied expression, struck me right then as it did everyone else in the room. It was theatrical. It was performance. It felt like this could really lend itself to the screen.

ON THE LIVES OF THE POETS

The original idea was a film about six poets. To have a story of six interconnected poets who somehow knew each other, and a weaving together of their lives and works. I had seen a documentary, Our City Dreams (2008) by Chiara Clemente, about five different painters: Kiki Smith, Ghada Amer, Swoon, Nancy Spero, Marina Abramovic. I began with Anne Waldman and found out quickly that poets constellated around her—anyone who has ever encountered her knows the power of that. She had these interconnections with the other poets I had thought to include—Ann Lauterbach, Alice Notley, Leslie Scalapino, Lyn Hejinian, Bernadette Mayer, Akilah Oliver, Eileen Myles. It quickly became apparent that Anne had so much going on, so many different varieties of events and collaborations, and she welcomed me in. She was like an umbrella to everything that was happening in the poetry scene.

ON TANGLING PRACTICES OF LIFE AND WORK

By documenting Anne I was living with her new works as they came out, and I got to be very immersed in them. I would read them, but I would also hear them performed and spoken about—and I would talk with Anne about them. And even though she wasn’t teaching her books, necessarily, she would talk about her work when she taught, and would always introduce her poems. I began to see just how the themes of all the books were entangled. With Jaguar Harmonics (2014), her book composed from notes from an Ayahuasca ceremony with the Indigenous Taíno people—she had just gone through cancer at the time. In Voice’s Daughter of a Heart Yet To Be Born (2016), Anne is working with Thel, a character from the William Blake poem, The Book of Thel. She wants to bring the unborn spirit of Thel into experience—into the world—into the Anthropocene generation. So, chronologically, although she had the ceremony experience after she had recovered from cancer, she wrote Voice’s Daughter of a Heart Yet To Be Born while in recovery. That also becomes part of writing Thel. The whole wide range of everything is contained in each work. And these works allow you to enter them from wherever you’re coming from. You wouldn't have to know any of that. It’s just this unfolding.

ON PULLING FROM THE ARCHIVE

I tried to steer clear of too much archival in the beginning, because I wanted to document freshly. I wanted it to be of this period. I had begun going over to Anne Waldman’s house, all those years, and so I had seen all the art and the poetry artifacts and the photographs—it’s all part of her world. So it was inevitable. The archive became interwoven with the project of the film, and I found myself motivated to search for materials and ask for things, this photo or that photo, excited to come upon a photograph I hadn’t seen before. Early on, the artist No Land brought to my attention the film by Bob Dylan Renaldo and Clara (1978), which features a performance by Anne reading her poem “Fast-Speaking Woman.” Ultimately we sourced archival materials from many art, film, poetry, and personal archives. To name a few: Larry Fagin’s Portraits and Home Movies (1968–89), Costanzo Allione’s film Fried Shoes Cooked Diamonds (1978), JA Hinojosa’s Dicen Que Estamos Borrachos (1975), Nathaniel Dorsky’s Hours for Jerome (1982), original Super 8 footage of Anne by poet Lee Ann Brown, cine-poems and recent footage by Natalia Gaia and No Land, The Poetry Project and Naropa Audio Archives, Anne Waldman’s personal family archives, and original artwork by George Schneeman from her home. What I’ve done in this film, in the end, and this hearkens back to the archival question, is gather material—and then find Waldman's arc. I didn’t start off with the archival project at first, but then I opened to it. And it kept opening and opening.

ON MAKING A TIMELESS DOCUMENT

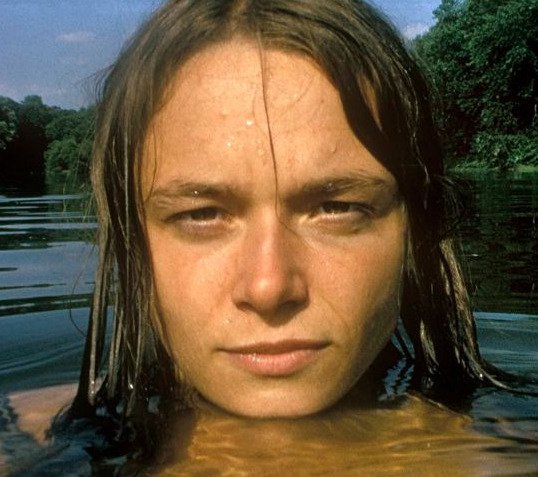

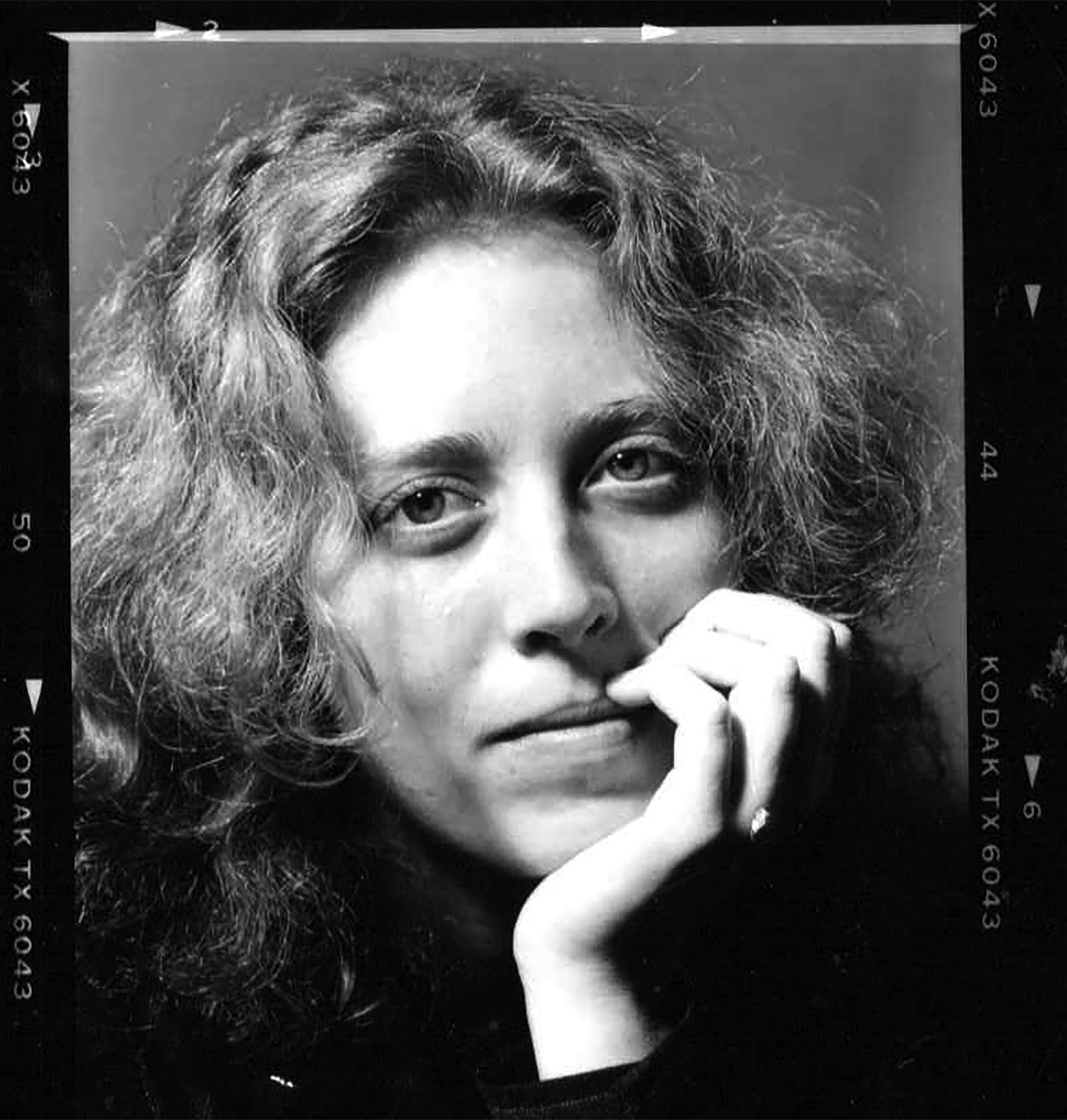

The treasure of having six photographs by Gerard Malanga of Anne in her youth. One is on the balcony of the Union Square Warhol Factory in the white blouse, and it just reads: Poetess. You see already the serious work happening in her mind. There are two with her and her mother, Frances, and one with her father and her mother on either side of her. But in all of Malanga’s photographs, the gaze is timeless. I’ve always wanted the film to have some aspects of timelessness. A timeless document. And a different approach to still images from the archival past. I was inspired originally by an image in a film by Nathaniel Dorsky, Hours for Jerome (1982). I asked him to use the scene of Anne emerging from the river—that’s the first image in our film. And Dorsky, understandably, didn’t want to share the moving image, but he made a still image. And he allowed me to use the still. When I first saw that scene in the theater I thought: “This is a timeless document. And the bar has been set. If our film could just touch that.” I thought it was a minute of her coming out of the river. But it’s very short—a matter of seconds—not even a minute. To me it seemed like five minutes. It had that eternal quality.

ON HER ROLE AS POET-FILMMAKER

I studied poetry in college, and then I came to New York in the nineties and started working at Gotham Book Mart and Grand Street magazine, and began going to all the poetry readings. That’s when I got wind of Anne Waldman. She was doing a workshop at the Poetry Project and gave us an assignment of writing a litany poem—but we had to rant our litanies—and we had to do it collaboratively. It’s been a huge learning curve, both in filmmaking and learning this person. And studying her as a master poet, of course. As a poet myself, I would always have had this connection to this character—I have an innate understanding of this world of writers. So I haven’t felt like I was coming in from the outside, or like a voyeur ever. It’s always been: “I’m here because I was already here. And now I have a camera.”

ON CROSSING MACDOUGAL STREET

Where I live is across the street from Anne Waldman’s childhood home on MacDougal Street although I didn’t know it for a long time. And because her childhood home is across the street, and because that is her oft-headquarters for bringing books together, I did once time myself and film the walk over. To capture everything that came in between. That’s not why I chose to make the film but it has became representative of what has happened so many times over the past decade. Walking from my door to hers. And that scene eventually made its way into the film—me walking into Anne’s house, it has this lush, drunken quality, full of art, it’s her radio, playing opera, Pavarotti or something, and then the two of us sitting down together. I kept it and I didn’t try to reshoot it. That seemed like an outtake for a while. But I think it gives just the right amount of context for the rest of the film. I became interested in that kind of lifting of the fourth wall from other filmmakers, such as cinematographer, Kirsten Johnson and her film Cameraperson (2016), who has made a practice of showing her mistakes. The idea that those moments are part of the act of documentation. That raw quality, that quality of making mistakes, catching yourself off guard—and the idea of that itself being documentary-worthy.

ON DOCUMENTING AS WIDE A PUBLIC AS POSSIBLE

I didn’t start out setting a timeline for Outrider but it spans ten years exactly and 2020 felt like a good time to end it. The first year, Anne was writing the libretto for Red Noir, a play directed by Judith Malina at the Living Theatre, The Iovis Trilogy was coming out, she was doing Manatee / Humanity at Dixon Place, and she was traveling, improvising with musicians, and directing Naropa and the Poetry Project at St Mark's Church. This constant stream of action to follow. Someone could wrap that up quickly, if they wanted to, but I always wanted this sense of duration or accumulated depth. Because that’s what time does. And it takes time, that relational building. It requires a certain tenacity. To always be showing up. To everything. I filmed hundreds of poetry readings, performances, poet gatherings, collaborations. Every Poetry Project event. Went consecutive summers to the Summer Writing Program at Naropa. I conducted significant interviews with artists, musicians, writers, activists, and students, family, and friends of Anne’s—Cedar Sigo, Emma Gomis, Vincent Broqua, Omar Berrada, Ed Bowes, Eleni Sikelianos, Devin Waldman, Ambrose Bye, Cecilia Vicuña, Lee Ann Brown, and others. And then there are performances and archival footage in the film of Allen Ginsberg, Bob Dylan, Diane di Prima, John Giorno, Laurie Anderson, Bernadette Mayer, Meredith Monk, Alice Notley, Ted Berrigan, Patti Smith, Eileen Myles, Cedar Sigo, Cecilia Vicuña, Thurston Moore, Daniel Carter, Pat Steir, Randa Haines, Douglas Dunn, James Brandon Lewis, No Land, M. NourbeSe Philip, Lewis Warsh, Erica Hunt, Anthony Roth Costanzo. Some things were magical and I never could have imagined, and had a life of their own—like being invited to go along to Morocco with Anne as she was working and teaching there. That proximity and living together, it opened up a whole new relational space for us to go from there. Lately, it’s been more of a friendship—one where I don't film her.

© Allen Ginsberg

© Gerard Malanga

© Nathaniel Dorsky

ON LIGHT AND COLOR

The Maitri rooms at Naropa—which Anne walks us through in the film—are a part of Buddhist psychology, five differently colored rooms representing five Buddha-Family traits, which intensify different wisdom energies and psychological states of deep awareness in you. We already had the colored rooms, that evocative visual poetry of light, color, that transforms your awareness. But in the editing, we get more distressed visual textures of color. The visual transformation that allows you to get into that experiential space a little bit more. To experience what the mind experiences when you’re in a space like that. There are other places of visual poetry. There is a lot with light in the film—and that was something that emerged naturally. We knew we wanted to include the lines from Outrider, Anne’s collection of essays, interviews, poems, and rants that became a manifesto for her Outrider lineage of poets. I decided I wanted to procure the exact typewriter that Anne had used. It was an Olivetti. And we had great fun typing the lines on that. And editor Melissa Huffsmith-Roth was able to bring a layer of light. that was on a book or a page, and bring it into a separate scene. So the light on the page became a motif in other scenes as well. Just the way the light was playing in places where it had no origin. Interspersing light where there was no light before.

ON ANNE WALDMAN’S DHARMIC PATH

If you’re a spiritual person, the Maitri rooms are a great place of instruction on how to be. And, for others, some people don’t want to be instructed in any kind of way. But it’s all part of her training. It’s part of her dharmic path. And that runs parallel to her path as a poet. I wanted the magic of the word to be at the forefront. Yes, she has this Buddhist training and she is navigating these themes around how to work with difficulties—in another interview she talks about the practice of Tonglen meditation, of taking in the pain of others with every breath and sending them relief in return. But, at the forefront, I wanted it to be about the word. Her role as a poet.

ON THE LONG, DARK NIGHT OF THE SOUL

Some of the most intimate moments—the part where her granddaughter is born at the beginning of the pandemic—and Anne’s raw vulnerability, working through the night that her granddaughter is born. She couldn’t be there in person because of COVID, so she was grieving a lot. She talks about those times when you feel paralyzed. It’s one of her themes. If you feel paralyzed—how do you work with that? And her way of working with that night is: You do what you do. And for Anne that is: to write, make tribute, to have a ritual, to have a ceremony, to enact it in some way, to mouth, to orally move it out into the world. It was one of the first times that she actually called me to document her. “Bring the camera.” That moment was a shift. “Come over—can you film this?” That is one of those moments where it feels like everything is lost but all is not lost. She’s just moving through it. And I feel it’s helpful to know how someone moves through it.

ON ANNE WALDMAN’S SIGNATURE DESIRE

She says that it’s an adventure story. And that she wants to take the whole ride. That’s a tattoo on the whole film. Her desire. Her desire is the through-line of the whole film. She was asked in 1978: What is your desire? And she answered that question. She desires all these things: Activism. The Practice of Poetry. There’s two whole paragraphs in which she answers it. In a way it’s not her desire for, just her desire. Period. And then it’s everything that her life has been. She did create her own reality.

We all have that. We all have that desire that carries us forward. But hers is very particular to her practices. It’s her originality, her particularity, her signature desire. Like her son says: She just never stops. I think Anne is constantly carried forward because it is just part of her nature to be restless. To continue to create and make things. In the documentary she does say: “I identify with action and speed, just keep moving things forward.” For other people, it might be perfectionism, but not for her. It’s staying generative. Not sitting on your laurels. And not stopping. Just continuing to write and perform.

—Alystyre Julian

Outrider premieres at Anthology Film Archives April 2025. For tickets and festival dates see below. Outrider premieres at Anthology Film Archives April 1–3, 2025

〰️

Outrider premieres at Anthology Film Archives April 1–3, 2025 〰️